By Laurence Mound (CSIRO Entomology, Canberra)

The thrips, or Thysanoptera, are small insects in which adults usually have very narrow wings with long fringing hairs. Although commonly considered flower insects, due to a northern hemisphere literature bias, worldwide about 40% of thrips species feed only on fungus in leaf-litter or on dead twigs, and about 30% feed only on green leaf tissues. Many of the flower-feeding species, such as western flower thrips and onion thrips, are important horticultural pests. On Acacia flowers, a few thrips may be found occasionally, but in Australia there has been a massive radiation of highly specific “leaf-feeding” thrips in association with the phyllodes of many species, particularly those from sections Juliflorae and Plurinerves. In addition, an unrelated thrips species induces galls on one Indian Acacia and a second on an African Acacia.

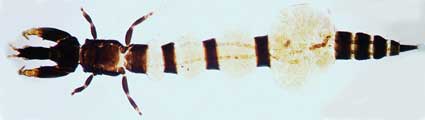

Kladothrips maslini female from near Lismore, New South Wales;

one of only two gall-inducing members of this genus found outside

the Australian arid zone.

Two major groups of thrips are distinguished. In the first group (suborder Terebrantia) the adult females have a saw-like ovipositor that is used to cut into plant tissue and insert each egg one at a time; this group includes most of the pest species of thrips. In the second group (order Tubulifera ) the females lay their eggs on the surface of their food plant, commonly in groups. The young stages of thrips look rather like wingless adults, and there are two such larval stages in all species, followed by two (three in Tubulifera) non-feeding pupal stages in which the organs of the body are reorganised into the adult condition. Although adult thrips usually have wings, in many species adults are wingless, and in other species both winged and wingless adults occur. The most curious features of thrips, apart from their fringed wings, are their tarsi which have an inflatable adhesive bladder, and their asymmetric mouth parts. Insects usually have a pair of mandibles, but in thrips the mandible on the right hand side of the head is resorbed during embryonic development, and the left mandible is a pointed structure that is used to make a hole in a leaf. The paired maxillary stylets, co-adapted to form a tube, are then inserted through this hole and the contents of plant cells are withdrawn one at a time.

More than 250 species in 35 genera of the Tubulifera subfamily Phlaeothripinae are now known from Australian phyllodinous Acacia species, and these thrips are not found on any other plants. These Acacia thrips appear to constitute a single evolutionary lineage that has radiated and diversified on these plants (Morris et al., 2002). One group of species induces phyllode galls, and another group are kleptoparasites that invade these galls. One remarkable and highly diverse group comprises species that construct their own domiciles by gluing or sewing together two or more phyllodes to provide a shelter within which to feed (Mound & Morris, 2001), and a different set of kleptoparasitic species has involved that usurp these domiciles (Mound & Morris, 2000). The largest suites of species comprise opportunists that invade abandoned shelters, such as the leaf mines of beetle and moth larvae, and old thrips galls.

Gall-inducing thrips

Foundress and soldier daughter of a typical eusocial Australian

gall thrips on Acacia.

One of these Australian genera of thrips includes at least 25 species, each of which induces galls on the young phyllodes of particular Acacia species. In some of these gall-inducing thrips the first generation produced by the winged gall-foundress is small, and the adults develop as wingless 'soldiers' (Kranz et al. 2001; Wills et al. 2003). In some species, these wingless individuals defend the gall from invasion, particularly from the kleptoparasites of the genus Koptothrips, but in other members of the same genus there is less evidence of defensive behaviour (Perry et al. 2002). The second generation within these galls is of fully winged adults that disperse and induce further galls. A very different life-history strategy has been adopted by several other species of the same genus of thrips. In these, the gall-foundress becomes physogastric with a greatly expanded abdomen, and then produces a single generation that in some species may comprise as many as 1000 individuals (Crespi et al. 2004).

Physogastric foundress of a non-social Australian gall thrips on

Acacia.

Domicile-creating thrips

Two Acacia phyllodes glued together by a thrips to create

a domicile (left). Domicile opened to expose thrips adults and larvae

(right).

In contrast to the galling thrips, a large number of species in six different genera construct their own domiciles, rather than induce plants to do this for them. They do this by gluing or sewing together two or more phyllodes to produce a small space, within which they can breed and feed. Some species produce a glue-like product from their anus to fix together two flattened phyllodes face to face, whereas others use a silk-like product to hold together two or more narrow or needle-like phyllodes. At least two species are known to weave onto the surface of a phyllode a flattened tent from the silk that they secrete (Mound & Morris 2001).

Kleptoparasitic thrips

A kleptoparasitic species of the genus Koptothrips that invades

Acacia thrips galls.

The Acacia thrips galls are invaded and usurped by kleptoparasitic thrips of the genus Koptothrips. These invading thrips kill the original gall thrips by stabbing with their fore tarsal teeth, and then breed for one or more generations in the galls that they have usurped, sometimes producing large populations. Although kleptoparasitic, these thrips are phytophagous not predatory. Domicile-creating thrips also attract the attention of kleptoparasitic thrips, but these apparently do not kill their hosts. Species in the genus Xaniothrips use an array of stout setae on their abdomen to drive out from the domicile those thrips that had originally produced it, by thrashing their tail and walking backwards (Mound & Morris 1999). Adults of two other genera are presumed to use curious spade-like tubercles on their antennae to effect entry into the domiciles they are known to usurp.

At least one thrips species has evolved as a true inquiline, in that it apparently breeds within the colonies of a particular domicile creating species without unduly disturbing the original inhabitants (Morris et al. 2000).

A kleptoparasitic thrips of the genus Xaniothrips that invades Acacia

thrips domiciles.

Opportunistic thrips

An opportunistic species of the genus Dactylothrips found

in lepidopterous leaf ties.

At least 50% of the species of Australian Phlaeothripinae on Acacia are opportunistic in their habits, invading only abandoned galls, or abandoned domiciles of other thrips, or the abandoned mines or enclosures created by larvae of moths and weevils. Three genera of such species are now known to each include more than 30 species. Moreover, a further group of Phlaeothripinae species can be found in splits on the bark of young twigs, but most of these thrips species are very small and difficult to observe in the field (Mound & Moritz 2000).

Australian Acacia thrips relationships

Current evidence suggests that the entire suite of Phlaeothripinae on Australian Acacia species comprises a single lineage that has radiated subsequent to a single invasion of this genus in Australia (Morris et al. 2002; Crespi et al. 2004). The radiation appears to have been driven primarily by competition for small enclosed spaces that provide protection from insolation and dehydration in the extremely arid environment of central Australia, but also by the need for protection from the many and abundant ant species (Crespi & Mound 1997).

Non-Australian Acacia thrips

Only two specific associations between species of thrips and Acacia are recorded from areas other than Australia. Acaciathrips ebneri is specific to Acacia nilotica in much of Africa, and Thilakothrips babuli is specific to Acacia leucophloea in India. Both of these thrips are highly specific and induce terminal galls by feeding.

Further information

Visit Laurence Mound’s Australian Acacia thrips website.

References

Crespi B.J., Morris D.C. and Mound, L.A. (2004). Evolution of Ecological and Behavioral Diversity: Australian Acacia Thrips as Model Organisms. (Australian Biological Resources Study & Australian National Insect Collection, CSIRO: Canberra). This book, which contains a Botanical Annexe by B.R. Maslin titled "Classification and phylogeny of Acacia", is available for purchase online.

Crespi B.J. and Mound, L.A. (1997). Ecology and evolution of social behaviour among Australian gall thrips and their allies. pp. 166-180. In Choe, J. and Crespi, BJ (eds) Evolution of Social Behaviour in Insects and Arachnids. Cambridge University Press.

Kranz, B.D., Schwarz, M.P., Wills, T.E., Chapman, T.W., Morris, D.C. and Crespi, B.J. (2001). A fully reproductive fighting morph in a soldier clade of gall-inducing thrips. Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 50:151-161.

Morris, D.C., Schwarz, M.P., Cooper, S.J.B. and Mound, L.A. (2002). Phylogenetics of Australian Acacia thrips: the evolution of behaviour and ecology. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 25: 278-292.

Mound, L.A. and Moritz, G. (2000). Corroboreethrips; a new genus of minute apterous thrips (Insecta, Thysanoptera, Phlaeothripinae) from the bark of Australian Acacia trees. Invertebrate Taxonomy 14: 709-716.

Mound, L.A. and Morris, D.C. (1999). Abdominal armature in Xaniothrips species (Thysanoptera; Phlaeothripidae), kleptoparasites of domicile-producing thrips on Australian Acacia trees. Australian Journal of Entomology 38: 179-188.

Mound, L.A. and Morris, D.C. (2000). Inquilines or kleptoparasites? New phlaeothripine Thysanoptera (Insecta) associated with domicile-building thrips on Acacia trees. Australian Journal of Entomology 39: 130-137.

Morris, D.C., Mound, L.A. and Schwarz, M.P. (2000). Advenathrips inquilinus: a new genus and species of social parasites (Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae). Australian Journal of Entomology 39: 53-57.

Mound, L.A. and Morris, D.C. (2001). Domicile constructing phlaeothripine Thysanoptera from Acacia phyllodes in Australia: Dunatothrips Moulton and Sartrithrips gen.n., with a key to associated genera. Systematic Entomology 26: 401-419.

Perry, S.P., McLeish, M.J., Schwarz, M.P., Boyette, A.H., Zammit, J. and Chapman, T.W. (2002). Variation in propensity to defend by reproductive gall morphs in two species of gall-forming thrips. Insectes Sociaux 49: 54-58.

Wills, T. E., Chapman, T. W., Mound, L. A., Kranz, B. D. & Schwarz, M. P. 2003. The natural history of Oncothrips kinchega, a new species of gall-inducing thrips with soldiers (Thysanoptera, Phlaeothripidae). Australian Journal of Entomology XX